In this Article:

Old superheroes never die

Interesting times over at DC comics. It’s easy to forget that very recently Dan Didio departed the company – and honestly, “Marvel Time” has nothing on COVID-time – but since then the end of the affair with Diamond distribution has overtaken reflections on his long tenure at the company.

Also, many comic creators and company employees are, it turns out, total creeps.

At any rate, Didio is vanishing in the rearview of the Time/Warner owned comic publisher. But in late June, Jim McLaughlin published an interview with Dan Didio on GamesRadar. The lede of this second part (of a feature split into three articles) focuses on Didio’s hatred of the character Nightwing, or Dick Grayson.

The discussion itself is more an insight into the market pragmatism Didio tried to apply to DC’s publishing line. Whatever a DC fan’s perspective on Didio might be, it is fair to claim the man as a genuine fan of comics in all their messy lore. He is also someone who acknowledges the struggling economic reality of the industry.

He talks with some passion about defending obscure mid-tier New 52 titles – for those not in the know, this was a publishing event in 2012 when DC comics relaunched their whole line with 52 revamped titles featuring new origins for their heroic characters. Hearing Didio go to bat for I, Vampire of all things – well I gained a wee bit more respect for the man.

Even if it is spin.

Eventually McLaughlin does ask Didio directly about the ‘hating Dick Grayson’ thing, and while the former publisher admits this was largely for theatre, he does say:

With…Dick Grayson — and this is the same with Wally [West]— people loved them because they aged with them, so they feel this affinity that these guys have grown up with them. The problem is that much like Batman and Superman, now Dick Grayson and Wally West have to stop aging, because they’re going to pass their mentors.

Dick Grayson’s going to get older than Bruce Wayne at some point, because Bruce doesn’t age and Dick Grayson’s going to be the older guy if he does keep growing up. Therefore, those things constantly force the reboots that we’re faced with, because it creates these log jams and these multiple interpretations of characters all sharing the same name.

Now this fascinates me, because it points to a couple of issues that have continued to dog the US comics market in my lifetime.

Firstly, comic fans continue to age upwards. Didio discusses how in the old days comic books would continually reintroduce characters, because waves of young readers would have come and gone in a much shorter period. The turnaround almost gave a perpetual present to the stable of characters. Batman was perennially in his late twenties or early thirties. He was not old, despite being an iconic character for decades when Steve Englehart introduced the Joker Fish storyline in 1978 (Detective Comics #475).

Secondly, this concern with the aging of superheroes has always struck me as odd. One point of comparison reviewers sometimes make to long-running comic series is that they are like soap operas. Uncanny X-Men, for example, during the Chris Claremont era, was a soap opera with similar dangling plot-threads and sudden unforeseen status quo shifts.

In soap operas the actors visibly age. Sometimes they are replaced, sure. But in a the Bold and the Beautiful, despite the wonders of plastic surgery, we can witness the characters getting older. And the viewers are getting older too. Or some are discovering the show for the first time and come to love the cast of characters regardless.

Here is my question. Why not allow comic book superheroes to get older?

Frank Miller claims he was inspired to write The Dark Knight Returns when he realized he was older than Bruce Wayne. He moved the Batman into the future, so he could write a Batman with more life experience than himself. While inspiring a classic Batman story, Miller’s admission has always struck me as resembling a midlife crisis, but bound up with a fictional character.

Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon have John Constantine turn 40 in Hellblazer #63. Again, I’m amused that Ennis was 23 at the time of publication, his world-weary protagonist bemoaning his advancing age. But later writers kept the date of John’s birth canonical, and so readers witnessed the street magician enter his 60s….before Dan Didio’s New 52 event reversed the process and reintroduced a young thirtysomething Constantine.

This apparent gerontophobia makes me curious. If, as Didio asserts, the issue is the sidekicks getting older means readers will see young wards grow into mature men and women, while their mentors are unchanged, what if the solution is right there.

What if the superhero character is a franchise?

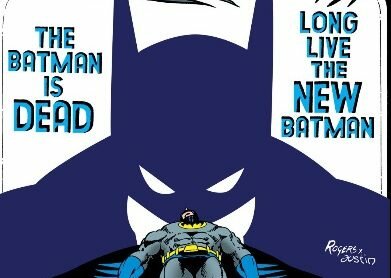

Say Batman hits 50 and the knees are popping and he’s taking too long to recover from a typical bout, well there’s Dick Grayson waiting to don the cowl and become Batman.

We’ve already seen this happen under Grant Morrison’s run on the character, but that same storyline was largely about how DC would not allow Bruce Wayne not to be Batman. In a sprawling metanarrative about how central Batman is to the history of his fictional universe, the eventual conclusion Morrison comes to, using authorial narration, is:

All I really need to know is this: Batman always comes back, bigger and better, shiny and new. Batman never dies. It never ends. It probably never will. [Batman Incorporated #13]

Morrison in pulling back from the commercial logic of franchising out the Bat to a number of other vigilantes, is making a comment on how the publisher will not allow any such fluctuation. Bruce Wayne must be Batman, because the product DC is selling features a character called Bruce Wayne, who is Batman.

If you’ll indulge me, I wrote about this storyline previously in a collection of essays titled Grant Morrison and the Superhero Renaissance [McFarland, 2015]:

[Morrison’s] story revolved around a genuinely global organization bankrolled by Bruce Wayne. Wayne’s strategy is to execute socially progressive crime-fighting measures across the world through the franchising of the Bat-band, applying the model of a corporation to the work of a superhero. Batman’s alter ego, Bruce Wayne, never had to hide behind a mask. Morrison [has him realize] he only had to announce himself as the chief shareholder in the Bat.

I still consider this to be one of the most interesting ideas featuring a DC comic superhero in recent years, because it could easily resolve these concerns of Didio and a twentysomething Frank Miller. Let the heroes pass on their alter egos to younger men and women. Let the franchise *be* the secret, with each superhero becoming a variant of the Dread Pirate Roberts.

And in that implicit citing of franchising and brand identities, Didio’s balancing act between market realities and fannish love of these characters could be resolved.

Just a thought.