Disclosure: Some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning, at no additional cost to you, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase through our links.

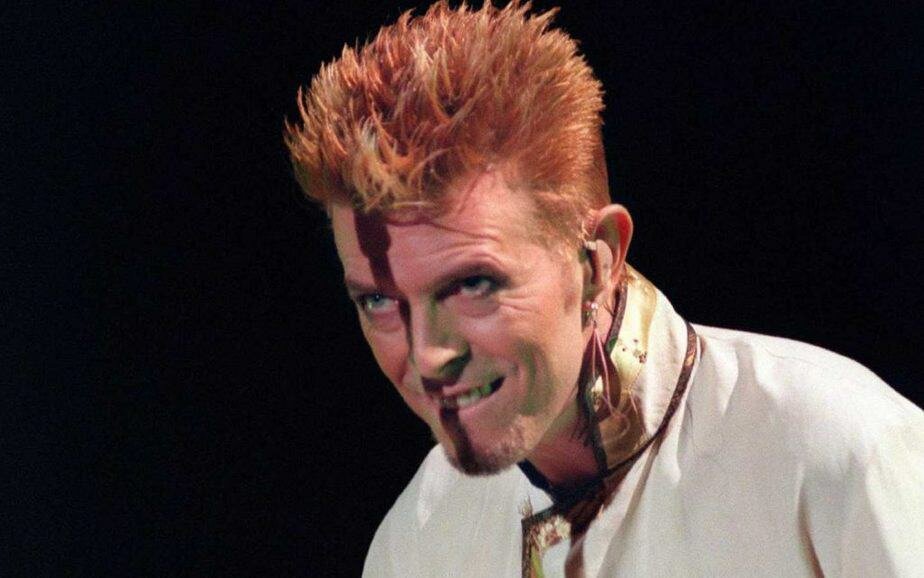

Bowie in Stardust (2020)

Perhaps a movie about the life of David Bowie four years after his death – an event many assumed set in motion the annus horribilis of 2016 – was simply too soon. But the reviews are in for Stardust, directed by Gabriel Range, and they are not kind. If there is a consistent criticism, and one that can easily be detected from the trailer, it’s that Stardust reduces Bowie to a type.

The desperate, aspiring rock star. Fodder for the kind of deathless musical biopic that should have received a stake through the heart courtesy of the hilarious Walk Hard (which has its own Bowie nod). There’s mention made of Bowie as a shapeshifter performer, but it’s presented as a neat aspirational note for this film to resolve on a par with the kids struggling to make a hit record in That Thing You Do!.

When we talk about Bowie the shapeshifter, what do we mean? It was not simply a matter of his musical style shifting and changing down the years, or indeed his sartorial leaps from Mod to Martian, and then back again to coked up banker.

It’s that Bowie as a creator had an outsized imagination that he would explore in whatever direction it took him. There’s a playfulness and intellectual curiosity to his style of invention that defies the commercial categorisation of Bowie qua performer. In his smashing together of talent and amateurishness – he was a singer, a dancer, a mime, an actor, an artist: occasionally ambition outstripped ability – Bowie’s genius was in becoming a self-defined popular culture object.

Comics have the capacity to present on the page a version of reality that can be as extensive as the artist wishes. They are magpie-like in terms of style, narrative technique and presentation. Bowie as a fellow-traveller of the comic book would seem to be the perfect fit.

The medium in English-language countries went through its own Pop Art ructions, from Lichtenstein’s ‘borrowings’ to Batman ’66 and its popularity with the Factory set. The American comic book for a time tested the limits of the commercial viability of the form (e.g. Bob Haney’s comics alone contain such multitudes).

Bowie’s Diamond Dogs as a graphic narrative

And it’s tempting to find in Bowie’s visualisation of a proposed film version of Diamond Dogs the makings of a graphic novel.

Like Jack Kirby, he slams together futurism and urban poverty from the previous century. Both the former Ziggy Stardust and Jack ‘The King’ sketched out the carnivorous exploitation of the powerful on a civic populace.

Bowie’s narrative of Halloween Jack and his Diamond Dogs, with its fusion of Fritz Lang and George Orwell, landed not on the cinema screen, or the comic page, but instead became a stage show. The arduous tour led to a series of on-stage malfunctions. A section of the Diamond Dogs stage even managed to land in a Florida swamp. There’s that ‘outsized imagination’ again, too big to be contained by panels or frames, or indeed the pop music industry of the 1970s.

It’s no wonder I find the depiction of Bowie in Stardust so small and limited.

So, if Bowie, in his hermetically controlled fame, never indulged in comics as a creator, his influence on the medium is easier to detect. Perhaps Mike and Laura Allred are the most specific inheritors of classic Bowie imagery, and Bowie: Stardust, Rayguns & Moonage Daydreams is the apotheosis of their series of tributes. However, creators from Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison and Kieron Gillen, to indie creators like Con Chrisoulis, have all demonstrated his continuing influence on comics.

Although if there was anyone in comics Bowie most resembled, I reckon it’s Stan Lee. Both were men with a vision – and a gift for arrangement. They both played to the strengths of their collaborators and stamped their unmistakeable brand on the resulting product.

Sandman – Neil Gaiman and Sam Kieth – Bowie as Lucifer

So, the story goes Gaiman insisted on Lucifer being portrayed as early Bowie. It’s an interesting model, and artist Sam Kieth obliged.

In Sandman we find an initially vindictive Lucifer, who is dismissive of Morpheus, but eventually they come to an arrangement. Lucifer quits Hell altogether, moves to LA and sets up a piano bar named Lux. The storyline then involves Morpheus having to resolve the power vacuum left in Hell. Perhaps in that we see the true relationship between Gaiman and Kieth’s Lucifer and Bowie – a character who realizes he is not in control, and simply quits to reinvent himself.

Also, it goes without saying that Mike Carey and Peter Gross’s run, with Ryan Kelly and Dean Ormston, on the comic Lucifer, explores the idea of the eponymous character as an avatar of freedom in much greater detail. And Tom Ellis’s pansexual version of Lucifer in the television adaptation is a lot more fun than viewers had any right to expect!

The Wicked + The Divine – Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie – Lucifer (again!)

It’s interesting to note that Gaiman and Gillen are both comic writers with backgrounds in music writing. However, Gillen’s partnership with Jamie McKelvie in books like Phonogram, The Immaterial Girl, and then The Wicked + The Divine has explored the spectrum of pop music and fame narratively.

There’s a self-consciousness to Gillen’s script that has ‘Luci’ call out her own reliance on the rock culture of the 1970s. And McKelvie delivers on that, styling her after Bowie in his heyday.

Which informs The Wicked + The Divine itself, as a dialogue on the shifts of pop culture from the baby boomer favourites to the mutations of the always online fandoms of today. And part of the trick pulled by Gillen and McKelvie here is to have Lucifer be left behind, just as Bowie himself seemed to almost drift out of public consciousness before his last staging of Black Star.

Batman and Robin – Grant Morrison and Frazer Irving – Bowie as The Joker

Morrison has featured the Joker in their various Batman runs – notably a coquettish and flirty take in Arkham Asylum with Dave McKean. In Batman and Robin the Joker is disturbed by the void left by Final Crisis, namely Bruce Wayne vanishing into the timestream courtesy of Darkseid (comics everyone!).

Joker drops his persona and adopts an entirely new one, Oberon Sexton. There is something fascinating here, the Joker responding to Dick Grayson becoming Batman in a manner similar to an allergic reaction. The status quo of the book has changed, so the Joker changes – but he does so consciously.

Morrison’s version of the Joker is the most indebted to Bowie’s musings on sanity and the claim that Bowie was simply open to the idea that his self was a construction, whereas most of us delude ourselves into thinking otherwise. Hence Ziggy Stardust, Halloween Jack, Soulman, The Thin White Duke – Morrison’s Joker claims to be equally adaptable.

Frazer Irving’s art features the Crown Prince of Crime in a series of grinning extreme close-ups, the panel acting like a camera lens. This is Scary Monsters-era Bowie, his commedia dell’arte costume translated to an elaborate gravedigger costume worn by the Joker.

There’s a rich vein of reference here in the collaboration between Morrison and Irving. But the Joker’s claim that he is ‘supersane’ owes less to Bowie’s Situationist performativity, and more a literal rendering of the interviews from his coked up, Nazi-inflected ‘Thin White Duke’ era.

As a tribute to Bowie, Morrison’s use of the Joker is a reflection of Kieron Gillen’s self-conscious addressing of Boomer taste in The Wicked + The Divine. As time passes further from the seeming bleeding edge novelty of The Invisibles, Morrison’s comics seem increasingly indebted to nostalgia (see also their current Green Lantern run as a comment on the Dennis O’Neil ‘Hard-Travelling Heroes’ era, 50 years on).

Bowie as Bowie

The big question is – should I buy Bowie: Stardust, Rayguns & Moonage Daydreams by Steve Horton and the redoubtable Allreds?

And the answer of course is yes. This is a stunning book. It delivers on the promise of Mike Allred’s clear love of all things Ziggy Stardust since Red Rocket 7. And while Mike and Laura Allred work on Stardust, Rayguns & Moonage Daydreams is a delight, suitable for a coffee table in any home – there is again a certain flatness to the attempt by Horton to render Bowie’s life as digestible narrative. Where the book excels is its surreal fugues, the artistic interpretation of the Allreds delivering something close to visionary excess.

I found Australian comic creator Con Chrisoulis’s Rebel Rebel more engaging in that respect, serving as well researched biographical reportage of Bowie’s early life.

The facts of young David Jones are fascinating in and of themselves, and there’s a compassion to the approach by Chrisoulis that is ultimately quite winning. In addition, the music recommendations in each chapter of the web comic are a nice mood setter. There’s a fascinating highlight involving Queen Elizabeth II, that reminds the reader Bowie was always meant to be a star. If you’re curious I’d recommend tracking down footage of school-age David Jones appearing in a news report, already aware of the camera and how to capture attention.

Néjib’s Haddon Hall: When David Invented Bowie, available from SelfMadeHero moves the focus to Bowie’s early attempts to become famous. It again has a sense of affection for its subjects, including Marc Bolan. Néjib is more interested in capturing a mood than pinning down Bowie like a dead butterfly, and accordingly, Haddon Hall is a book bursting with colour and flowing illustrations. A ‘paint off’ between Bowie and Bolan is a tantalising taste of what’s to come early in the proceedings.

Both Néjib and Chrisoulis spend more time on the singer’s relationship with his brother Terry, who has been committed during the sequence of time featured in Haddon Hall. And that is something worth bearing in mind, before Bowie became Bowie his life was already rich enough for a biopic without the need for pat homilies about striving to succeed. These indie creators use the space of the comic book page to draw out that human interest.

Which if any future adaptors of Bowie’s life are looking for a note, maybe it’s this – be interested, be curious, be strange. Be like Bowie.

Want more ?

RELATED ARTICLES:

Poppy: An LP and Graphic Novel Combo