About Halloween

Every year, millions of children – and adults, celebrate the ubiquitous holiday of All Hallows Eve, or Halloween. Costume parties and trick-or-treaters grace nearly every neighborhood in suburbia. However, the most anticipated aspects of Halloween are the ideas of transformation and releasing inhibitions. It’s a time when you can transform yourself into someone you ordinarily wouldn’t have the chance to be. Children get to be superheroes.

Teenagers harness the mischievous energy surrounding the night. And adults just want to eat their kid’s leftover candy. For six-year-old Michael Myers (Will Sandin), his transformation on Halloween night of 1963 would not only transform and define the legacy of fictious Haddonfield, Illinois, it would give birth to The Shape (Nick Castle). Or, as Tommy Doyle (Brian Andrews) says, “The Boogeyman!”.

Halloween (1978) was directed and memorably scored by horror legend John Carpenter, and co-written alongside long-time collaborator and producer, Debra Hill. The plot is simple: on Halloween night of 1963, six-year-old Michael Myers stabs his babysitting older sister, Judith Myers (Sandy Johnson) to death with a chef’s knife.

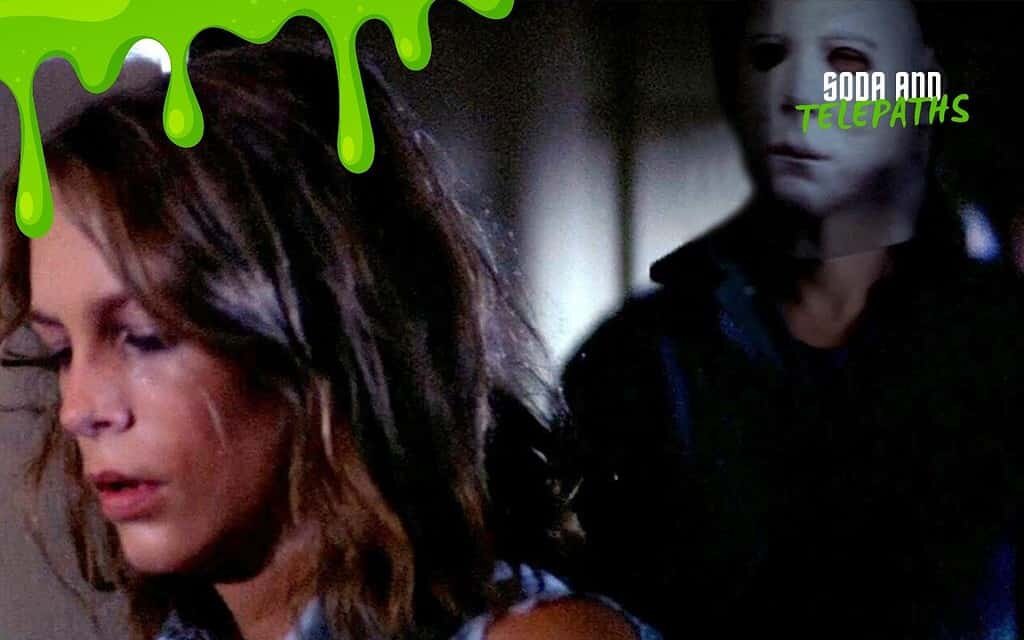

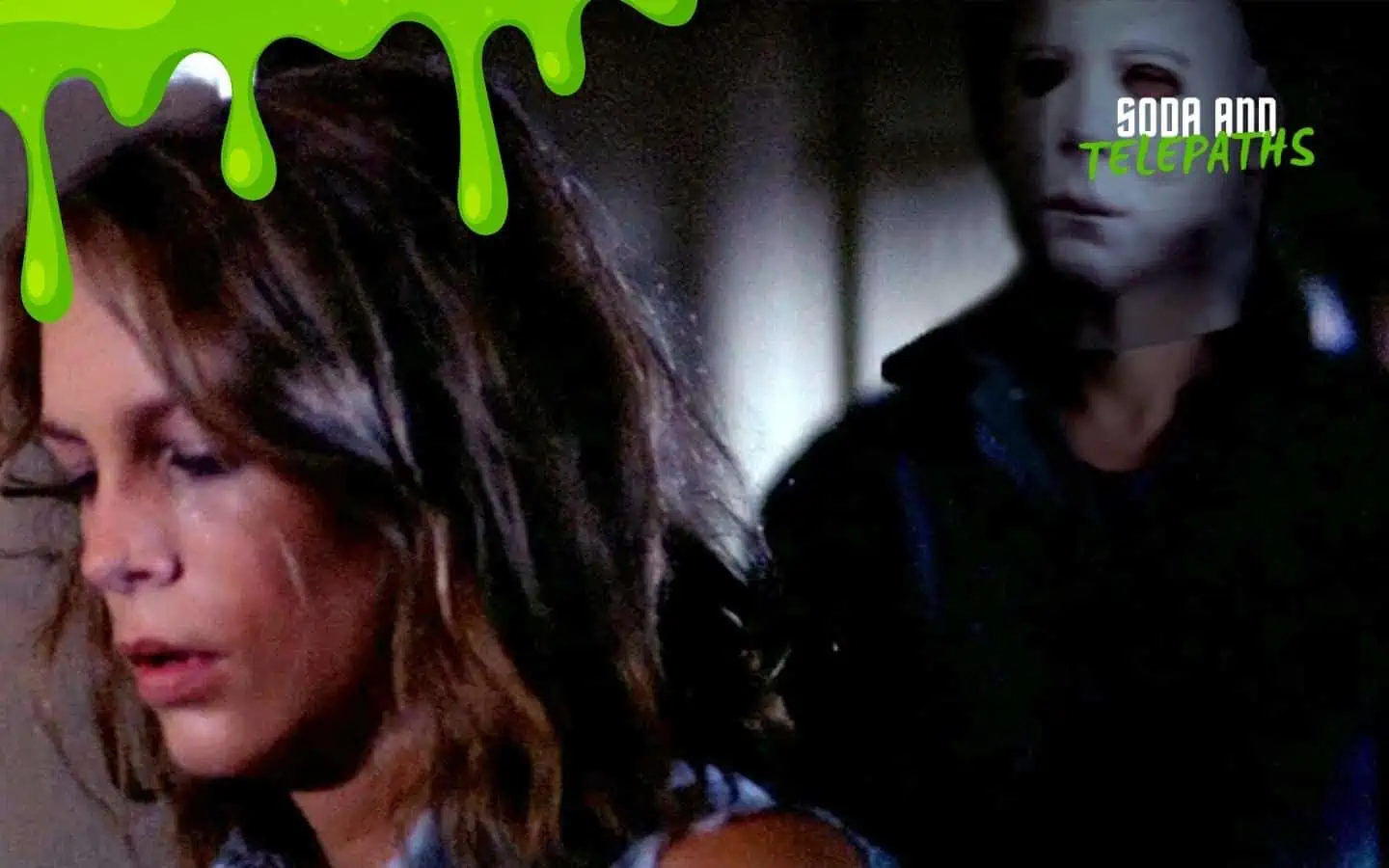

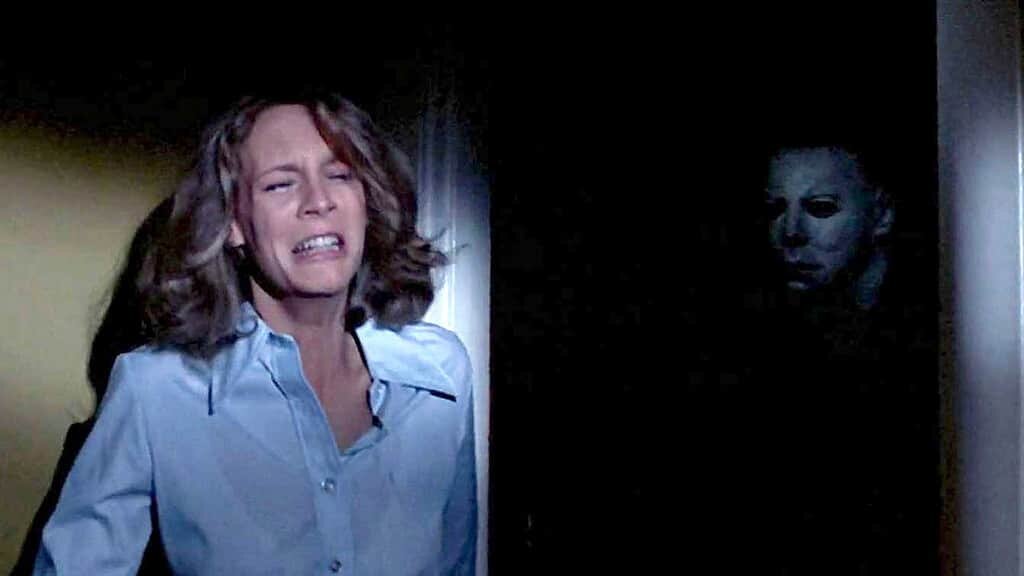

Flash forward 15 years later to October 30,1978 and an adult Myers (Tony Moran) has now escaped confinement from Smith’s Grove Sanitarium and returns to Haddonfield to continue his murderous spree. However, this time, his new obsession is Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis), a teenager babysitter, and her close-knit group of friends, Annie (Nancy Loomis) and Lynda (P.J. Soles). Hot on his heels, is Myer’s psychiatrist, Dr. Loomis (Donald Pleasence).

Throughout the day, Lori frequently sees The Shape following her and shares her concerns with Annie and Lynda, to no avail. Meanwhile, with Sheriff Leigh Brackett (Charles Cyphers) patrolling the streets of Haddonfield, Dr. Loomis returns to the Myer’s house and awaits The Shape’s return home. Later that evening, as Laurie is babysitting Tommy, Annie is across the street babysitting Lindsey Wallace (Kyle Richards). From here, The Shape’s plan to stalk and victimize his prey, begins. As The Shape roams between the Doyle and Wallace residences, it’s clear that Dr. Loomis is quite right – The Shape is nothing but pure evil.

Halloween Influences and Social Commentary

While the plot isn’t complex, and there are some tropes in Carpenter’s film that are commonplace in horror, the conventions and ideologies are anything but. Much of Halloween’s core theme orbits the notion of fate. In fact, Carpenter wants to make it very clear: this movie is all about fate. Every character here is dealing with some aspect of fate. And as Laurie’s teacher declares near the beginning of the film, “Fate never changes”. And with fate comes the fear of the unknown. We all know what happens to the girls who hone and utilize their sexuality in horror films (I’m looking at you Annie and Lynda). Or to the ill-fated characters who proclaim, “I’ll be right back”.

These characters’ destinies are written in the stars. Take the Myer’s old residence. When Laurie and Tommy are walking to school on the morning of Halloween, Laurie has to drop off a key to the Myer’s house, where Laurie’s father, Morgan Strode’s (Peter Griffith) realty company, Strode Realty, is hoping to sell the abandoned house of hell. Tommy is terrified of the house, while Laurie casually and fearlessly approaches the house to deposit the key. Aside from Laurie, it would be safe to assume that many of Haddonfield’s residents share Tommy’s sentiments and fears of the Myer’s house. And for what?

Not many of them have ever stepped foot into that house. But it’s the codependent relationship between fate and fear of the unknown that keeps people at bay. You’ve been dared to go into the Myer’s house? Proceed with caution, for you may not come emerge unscathed – or alive. Carpenter teaches us that fate and fear of the unknown are an unstoppable force and an immovable object, respectively. We can’t have one without the other.

Although Carpenter places fate front and center, voyeurism as well as sexual repression and identity permeate from many of the point of view shots. When six-year-old Michael spies on Judith from outside of the house and sees her boyfriend take her upstairs (and subsequently drops the clown mask that Michael dons while murdering her), the viewer can’t help but feel that Michael was triggered by the mere suggestion of intimacy.

Once the lights go out upstairs, Carpenter inserts a brilliant, sharp and pensive piece of his score to communicate this to us. And this is a great example as to why a film’s score is so important. It can narrate a story and propel a character’s point of view. For The Shape, there’s a sense that he fears intimacy and sees it as a threat to his existence. We seek to destroy what can destroy us. Hence, his relentless and obsessive pursuit of Lori. He must have made up his mind after stalking Lori on the way to school and hearing her sing the words, “I wish I had you all alone. Just the two of us”.

In terms of sexuality, Annie and Lynda are polar opposite characters in comparison to Lori. Throughout the majority of their time spent together, Annie teases Lori regarding her tame dating life. But we, as the audience, know better at this point. What Annie doesn’t realize is that she is fulfilling a self-prophesized fate of being the ill-fated and doomed sexually promiscuous character. Whereas Lori is the esteemed, wholesome final girl. And we know she is going to make it.

Why? Well, this is why character tropes are so important. Remaining a virgin until the end credits isn’t about being defiled in horror movies; it’s about remaining self-aware of your surroundings and weaponizing your intuition to survive. And this is exactly what Lori does. We will never look at a knitting needle the same way again. Thank you, Lori Strode.

Annie and Lynda have clouded their judgments with the illusion of sex. This is why the representation of final girls is heavily influenced by sexuality. When our minds operate from a place of primal instincts that seek to fulfill pleasure, our will to survive, and those instincts and skills, go dormant. This is what makes The Shape the ultimate predator. He doesn’t know any of that.

All he knows is to seek and destroy what he sees is destroying humanity. And he does that with his instincts. This is what has defined the bond between Lori and The Shape and has kept them fatefully tied to one another for so many years: they are both survivors and predators with killer instincts.

Halloween: The Retrospective Review

Unlike Rob Zombie’s ultra-violent 2007 remake, John Carpenter’s Halloween doesn’t flesh out Michael’s backstory. And I believe this was done intentionally. We never see any of Michael’s previous experiences prior to the events of that fateful Halloween night in 1963. Was Michael a victim of trauma and a product of his environment? Or was Michael born evil and hardwired for a life of chaos and destruction, and that was his fate that he could not escape?

I love John Carpenter’s Halloween because it lets us create our own version of Michael. Because as simple as his motives and urge for violent kills may be, Michael is still a meatbag covered in skin and bones, having a human experience – just like the rest of us. And if we are not taught to process our emotions in a healthy and productive manner, then all of our past traumas and repressed feelings of shame, guilt, and unworthiness, rise to the surface in, otherwise, uncharacteristic ways.

Metaphorically speaking, and no different than Michael, we all wear masks. How we portray ourselves to our family is not how we present ourselves to our friends, lovers, colleagues, and even strangers. We all have masks for different social groups and situations. It’s how we get by in our day-to-day lives. Without this self-regulating method, much of humanity would implode on themselves. Michael is referred to as The Shape because that’s who Michael has always been.

The mask not only represents his true face, but his persona as well. However, for Michael, he wears his mask proudly (and don’t you dare even think about taking his mask off). Even if we can’t make sense of it, it’s him showing up as his most authentic version. Even if that means that he is regarded as an apathetic and homicidal psychopath with no regard for human life. What we can learn from Halloween is that it’s okay to take off our masks and let ourselves see us as we truly are. It’s risky – and vulnerable. But it’s a hell of a lot better than tearing yourself apart from the inside out.

Have you seen Halloween?

What are your thoughts on Halloween? Have you seen it? Do you think Carpenter created a cult classic that redefined the modern horror slasher? Let us know on social media.